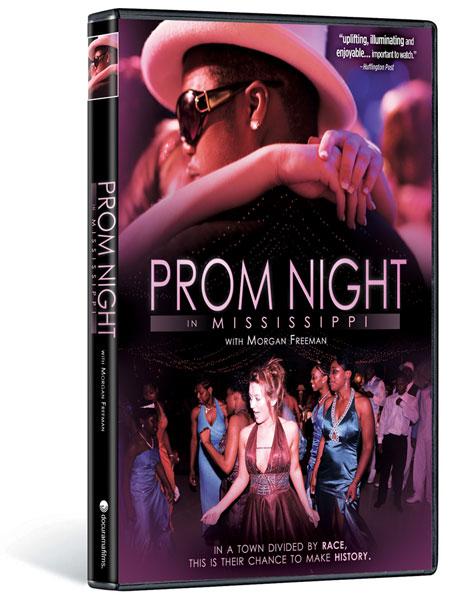

Prom Night In Mississippi

One town. Two proms.

Until now.

Prom Night in Mississippi

TO PURCHASE DVD’s OF ‘PROM NIGHT IN MISSISSIPPI’ USE THIS LINK.

Canadian filmmaker Paul Saltzman follows students, teachers, and parents in the lead-up to the big day. Morgan Freeman addresses the student body. Girls shop for dresses and get their hair done. Boys rent tuxedoes and buy corsages. These seemingly inconsequential rites of passage suddenly become profound as the weight of history falls on teenage shoulders.

ABOUT THE FILM

In 1997, Academy Award-winning actor Morgan Freeman offered to pay for the senior prom at Charleston High School in Mississippi under one condition: the prom had to be racially integrated. His offer was ignored. In 2008, Freeman offered again. This time the school board accepted, and history was made. Charleston High School had its first-ever integrated prom – in 2008. Until then, blacks and whites had had separate proms even though their classrooms have been integrated for decades. Canadian filmmaker Paul Saltzman follows students, teachers and parents in the lead-up to the big day. This seemingly inconsequential rite of passage suddenly becomes profound as the weight of history falls on teenage shoulders. We quickly learn that change does not come easily in this sleepy Delta town. Freeman’s generosity fans the flames of racism – and racism in Charleston has a distinctly generational tinge. Some white parents forbid their children to attend the integrated prom and hold a separate white-only dance. “Billy Joe,” an enlightened white senior, appears on camera in shadow, fearing his racist parents will disown him if they know his true feelings. PROM NIGHT IN MISSISSIPPI captures a big moment in a small town, where hope finally blossoms in black, white and a whole lot of taffeta. -David Courier, Sundance Film Festival

FILMMAKER’S STATEMENT: PAUL SALTZMAN

In the summer of 1965, I was in the Mississippi Delta doing voter registration work with SNCC—the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee—and, like many other civil rights workers, was assaulted and jailed.

Mississippi was known to us as “the belly of the beast” of southern racism and segregation. The KKK was strong there. The White Citizen’s Council—the “white collar Klan” as they were referred to—was strong there. And as a “northerner,” in fact, a foreigner, since I had driven south from my home in Canada, I was somewhat shocked to discover some of the great institutions of America: the Boy Scouts, the Girl Guides, the YMCA, the Howard Johnson, even washrooms and drinking fountains, were segregated in the south.

For over forty years I thought about how race relations might have changed, or not changed, since I had been there. In 2007, I decided to find out. I bought my first video camera and flew down to Jackson. I had no plan or script or funding. I just wanted to talk with ordinary folks, black and white, young and old, racist and not racist, and encourage them to share their stories and feelings around matters of race. After renting a car and driving around the Delta, where I had mainly been in ’65, it became a personal documentary, a road movie: ‘Return to Mississippi.’

I met Morgan Freeman and filmed with him at his home in the small town of Charleston, Mississippi, population, 2,100. He, too, had returned to Mississippi where he grew up, saying he felt safer there than anywhere else in America.

On the one hand, I learned that Mississippi had come further in race relations than any State in the Union since the ’60s—with the highest per capita black elected officials, black police chiefs and black fire chiefs. But then I found out something that seemed too strange to be true. I heard from a young woman that her integrated high school still held separate proms: one white prom and one black prom. If this was true, I wanted to include that as part of the film. I then learned that this prom was held in Morgan’s home town, and that a decade prior, Morgan had offered to pay to integrate the high school prom, but was rebuffed. I asked Morgan about it, and he confirmed the story. I asked if he was willing to try again, and he said yes. So a meeting was set up with Morgan at the school board office, and we began filming a second feature documentary: ‘Prom Night in Mississippi.’

Not knowing what would result, my wife and co-producer, Patricia Aquino, and I funded the shooting on our own. Tallahatchie County is the poorest in Mississippi and, likely, the poorest in the country. Some of the townsfolk were worried we had come to make them look bad. To win the confidence of the students, parents and school staff we moved to Mississippi and lived in the community for four months, culminating with the town’s first-ever, integrated prom.

Many of the senior students, black and white, impressed me with their openness and awareness. Their courage to attend their first “mixed prom” and to share their feelings about race gives me hope that we are indeed heading in the right direction, hope that more change will come in the next few years than in the entire 43 years since I was last in Mississippi.